For years, financial institutions across the country have been preparing for the implementation of the new current expected credit loss (CECL) accounting standard. A central driver of FASB’s action to CECL was criticism following the 2008 financial crisis that financial institutions had recorded losses too slowly and that past loss experience would be reflected in the allowance account on the balance sheet for longer than appropriate during a recovery.

In Q1 2020, SEC-filing financial institutions began reporting under the standard. Unlike the incurred loss model, the CECL methodology requires a forward-looking estimate that lends itself to a comparatively more quantitative approach. The wild economic uncertainty that emerged shortly after the standard’s effective date has created significant challenges to forecasting losses and making the macroeconomic assumptions that are necessary for CECL. The current conditions underscore the importance of the new standard and financial institutions’ preparedness to weather economic crises. Therefore, whether an institution is a 2020 CECL adopter or preparing for 2023, it’s essential to understand the implications the pandemic may have on their transition to the new accounting standard.

In Q1 2020, SEC-filing financial institutions began reporting under the standard. Unlike the incurred loss model, the CECL methodology requires a forward-looking estimate that lends itself to a comparatively more quantitative approach. The wild economic uncertainty that emerged shortly after the standard’s effective date has created significant challenges to forecasting losses and making the macroeconomic assumptions that are necessary for CECL. The current conditions underscore the importance of the new standard and financial institutions’ preparedness to weather economic crises. Therefore, whether an institution is a 2020 CECL adopter or preparing for 2023, it’s essential to understand the implications the pandemic may have on their transition to the new accounting standard.

2020 CECL adopters make adjustments

The passage of the CARES Act allowed for 2020 CECL adopters to delay the presentation of CECL’s impact on their financial statements until the end of the pandemic or Dec. 31 – whichever comes first. Remember, this is a presentation delay; the effective date has not changed. Financial institutions will need to continue running their CECL calculations throughout 2020 in order to determine the impact and make necessary adjustments. Garver Moore, Managing Director of Advisory Services at Abrigo, encourages financial institutions to stay the course with their chosen methodologies if they have already been audited and validated.

To substantiate financial institutions’ qualitative adjustments, Moore suggests using a discounted cash flow (DCF) model or remaining life methodology (also known as the WARM/WARL method, or Weighted Average Remaining Maturity/Weighted Average Remaining Life).

“Realistically, most models right now might be keyed to unemployment or GDP predictions, and most inputs on those terms are unprecedented – there’s no way you trained your model on a 15 to 20 percent unemployment rate,” Moore said. “You want to be really careful that what your model is saying makes sense in light of the pandemic.”

For institutions using a method that doesn’t accommodate for input-level projections, Moore suggests running a DCF model, where institutions can compare their current model against a more economic-based model to true-up the difference.

Financial institutions complying with CECL have tackled their approaches differently, and reserves for loan losses have varied, dependent on an institution’s:

• implementation methodology

• core assumptions and nature of lending practices

• estimates for future economic outcomes.

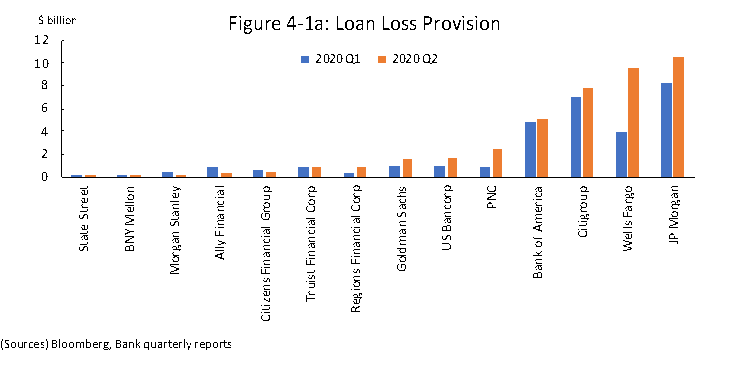

While institutions anticipated that their loan loss provisions would slightly increase by action of the accounting change, the coronavirus pandemic created a perfect storm for loan loss provisions.  In a recent podcast, Moore reflected on the initial Q1 reports – which revealed a significant uptick in loan-loss provisions, totaling nearly five times as much as the previous period. “You saw results that were all over the place, especially as we moved down the size range,” he said. “Some institutions made minor adjustments, saying ‘we’ll see,’ while others were more proactive about it.” Moore expects more convergence as future consensus emerges regarding impacts of the pandemic economy and as that consensus is reflected on more financial statements.

In a recent podcast, Moore reflected on the initial Q1 reports – which revealed a significant uptick in loan-loss provisions, totaling nearly five times as much as the previous period. “You saw results that were all over the place, especially as we moved down the size range,” he said. “Some institutions made minor adjustments, saying ‘we’ll see,’ while others were more proactive about it.” Moore expects more convergence as future consensus emerges regarding impacts of the pandemic economy and as that consensus is reflected on more financial statements.

Methodologies and considerations for 2023 CECL adopters

Preparing for CECL can be daunting for financial institutions of all sizes, but it presents an even bigger challenge for smaller financial institutions that may lack meaningful losses or loan history. The good news is that these institutions have a bit of reprieve during this unprecedented economic environment to see how CECL and the pandemic play out. While there are many methodologies for CECL that financial institutions can choose from, Moore frequently recommends DCF or remaining life methodologies to 2023 adopters. “Generally, either a DCF or remaining life methodology will allow you to solve most data problems that you’re going to end up having – especially if, I assume you’re a smaller, less complex institution by virtue of not having to adopt in 2020,” he said. “To be clear, other methodologies may be appropriate – our company supports several more – but our experience is a periodic, projective approach like DCF or Remaining Life allows the greatest flexibility in overcoming common data and experiential issues.”

A DCF or a remaining life approach will give institutions the ability to backtest results on a periodic basis. “These models make predictions like, ‘You will lose X over the next quarter, and then Y over the quarter after that, and Z over the quarter after that,’ so you can test it and have that intelligence quickly, which will be really helpful as we go through the pandemic and into the recovery.”

There is neither a crystal ball to know when the pandemic will wane nor any certainty as to how long economic recovery will take. To be sure, the current unprecedented conditions complicate forecasting, but financial institutions – whether 2020 or 2023 adopters – should not lose sight of CECL.

About the Author

Kylee Wooten is a content marketing manager at Abrigo.