In 2020, most SEC-filing institutions were required to move to the new current expected credit loss, or CECL, model. Following the 2007-2008 financial crisis, the CECL model aimed to provide more timely adjustments of reserve levels than the existing incurred loss method. Unlike the incurred loss model, the CECL model is forward-looking, estimating loans’ lifetime losses using reasonable and supportable forecasts.

In 2020, most SEC-filing institutions were required to move to the new current expected credit loss, or CECL, model. Following the 2007-2008 financial crisis, the CECL model aimed to provide more timely adjustments of reserve levels than the existing incurred loss method. Unlike the incurred loss model, the CECL model is forward-looking, estimating loans’ lifetime losses using reasonable and supportable forecasts.

Most financial institutions adopting CECL in 2020 had braced for their reserves to increase – even before the pandemic. But while COVID-19 created an entirely new, unforeseen challenge to estimating reserves for all financial institutions, it also reinforced the philosophy behind the new accounting standard.

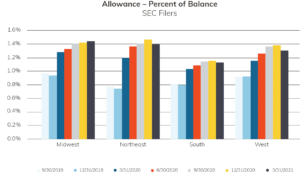

Abrigo analyzed proprietary loan-level data from financial institutions operating under the two different models and found contrasting stories of how reserve and provision levels progressed after the pandemic began. Neekis Hammond, Managing Director of Advisory Services at Abrigo, presented these findings during a recent presentation at ThinkBIG 2021.